Manure, a valuable asset that needs care

In many countries, manure from livestock is treated as a waste instead of an asset that needs care and good management. At the same time, the importance of improved manure management in relation to circular and climate-smart agriculture is widely acknowledged. NEADAP took up the challenge of identifying options to improve manure management in East African dairy farming systems with a focus on Kenya.

Let’s first have a look at the value of manure. Dairy cows convert forage and other feeds into milk, meat and calves and excrete manure as a waste product. This waste product consists of two fractions: urine (liquid fraction) and dung (solid fraction). Manure contains the same type of organic matter and nutrients that are in the feed the animal has ingested. Dairy cattle manure contains relatively large amounts of nitrogen (mineral and organic N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) and organic matter and smaller amounts of nutrients like calcium (Ca), sulphur (S) and micronutrients. This makes manure into a complete fertilizer.

However, the composition of the two fractions of cattle manure (urine and dung) is different. Most of the mineral nitrogen (urea) and almost all the potassium and some other minerals are excreted in the urine (liquid fraction). The value of this urea and potassium is comparable to synthetic fertilizer if it can be captured and applied appropriately. In practice, the urine often seeps into the soil in a cattle shed or where the dung is stored. The urea nitrogen is subject to volatilization once in contact with microorganisms in dung and soil that convert urea into ammonia. Therefore, nitrogen and potassium can easily be lost. Separate collection and storage of urine and dung will reduce the loss of nitrogen through volatilization.

The dung contains nearly all phosphorus, organic nitrogen and organic matter and other nutrients excreted by the animal. The organic nitrogen is mainly contained in the organic matter that is broken down slowly. In the Netherlands, it is estimated that 35% of the organic nitrogen will be available for plant growth in the first year of application. In the tropics with longer growing seasons and higher soil temperatures, this might be higher.

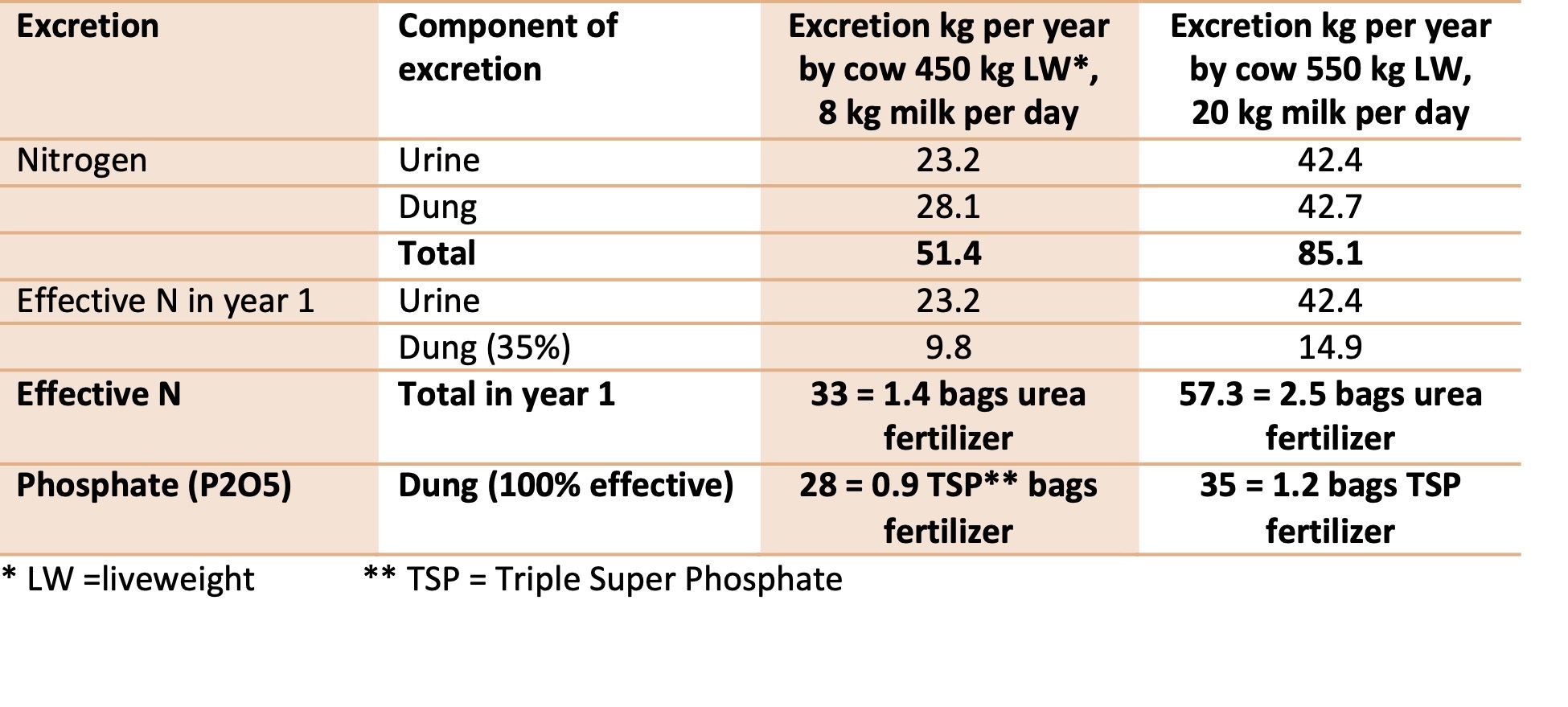

The amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus excreted by a dairy cow also depend on the feeding/production level of the animal. Table 1 shows calculations of nitrogen and phosphate excretion for two scenarios: a cow of 450 kg liveweight producing on average 8 kg milk per day and a cow of 550 kg liveweight producing on average 20 kg milk per day.

Table 1: Estimated excretion of nitrogen and phosphate (kg per year) by a dairy cow at two levels of feeding/production

The values in Table 1 show that the higher the feeding/production level, the higher the excretion of nitrogen (particularly in the urine fraction) and phosphate and as a result the higher the value of the manure. These values show an idealised situation of no losses occurring which is almost non-existent. As soon as manure is handled, losses will occur.

Manure management should reduce nutrient losses as much as possible and recycle nutrients to cropland. When cows are grazing, manure management is not really possible. The distribution of dung and urine is an issue. Spreading dung patches over the field will improve the distribution and effect of the excreted nutrients.

Therefore, manure management is particularly critical in situations where dairy cattle are confined and kept under (semi)-zero grazing. This is especially the case in the East African (peri-urban) intensive small-scale dairy farming systems. Losses of nutrients from manure will occur at different stages of handling: at time of collection, storage, during treatment and at and after application. Losses can occur through ammonia volatilization (nitrogen from urine mixing with dung on the floors of zero-grazing units, during surface application of manure), through nutrient run-off (manure flushed by rain from floors of barns, or from manure piles kept in the open; run-off of manure to public areas and water courses), by leaching (nitrogen and phosphorus during storage to deeper layers in soil or too high applications of manure on land) or by denitrification of nitrogen in manure storages or at time of application on land.

How can manure management be improved in small-scale intensive dairy farming systems?

A roofed, sloping floor of the walking area of a zero-grazing unit will reduce nutrient losses and improve the collection of dung and urine. Storage of slurry (the mixture of dung and urine) or, even better, a separate collection of dung and urine in a lined, closed or roofed storage will reduce losses through volatilization and run-off. Some farmers in the Limuru area in Kenya practise a separate collection of dung and urine from cows kept under zero grazing. Dung is collected and dried, stored or sold. Drying will improve the handling of the manure but will result in losses of mineral nitrogen by volatilization. The liquid is often not fully utilized. Separately collected dung and urine could be managed by drying or composting the dung so it can be stored and applied at the start of the growing season on cropland used for growing maize, vegetables, etc. The liquid fraction can be applied throughout the year on the forage crop after cutting.

Research has shown that the use of a cover on manure/solids stored in piles, heaps or pits reduces nutrient losses.

Treatment of manure in a biodigester will generate additional benefits in the form of gas, while most minerals will remain in the sludge or bio-slurry. This bio-slurry is very liquid and difficult to handle. Manure slurry (the mixture of urine and dung) is also liquid, but composting of bio-slurry and manure slurry can improve handling and hygiene while adding nutrients from other (organic) waste materials.

Previous research in Naivasha, Kenya, has shown that when slurry from dairy cattle was incorporated into the soil in between rows of Napier grass, the nitrogen losses were much lower than when the manure was just superficially applied because of a reduction of the losses by volatilization.

In conclusion: proper collection (separate collection and storage of urine and dung), good and short-term storage and quick application by incorporation into the soil will result in relatively low nutrient losses and improved long-term soil fertility, crop growth and economic benefit for the farmer.

NEADAP has piloted and demonstrated some manure management options in on-farm trials in Kenya. These options included the use of different covers, composting of manure and bio-slurry. Results and experiences are presented in this article.

To Learn more about Manure Management in East Africa

Please Contact: Our Solution Lead Bram Wouters at [email protected]

Authors

Bram Wouters

Solution Lead, Manure Management

Alex Mounde

Communication officer NEADAP